Subtotal $0.00

Just two days after the announcement of a ceasefire between Iran and Israel on June 24, 2025, with the direct intervention of US President Donald Trump, Iranian Defense Minister Aziz Nasirzadeh headed to China, where he held remarkable talks with his Chinese counterpart Dong Jun on the sidelines of a meeting of defense ministers of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) member states.

The visit was not only protocol, but also carried political and military messages at a very sensitive time, especially in light of escalating talk in Tehran of a clear desire to enhance defense cooperation with Beijing, as part of a broader strategy to counter US-Israeli pressures that culminated in the latest round of escalation.

With the end of this round of military confrontation, attention turns to China as the only international actor capable of balancing US influence in the Middle East without direct involvement, especially in light of China's strategic interest in maintaining the stability of the Iranian regime, as opposed to Israel's efforts, with Washington's support, to weaken or topple it.

Iranian-Chinese relations

Despite the ideological and systemic differences between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Communist Republic of China, the two countries have succeeded in recent decades in building a strategic relationship based on mutual interests in the face of increasing Western pressure, led by the United States.

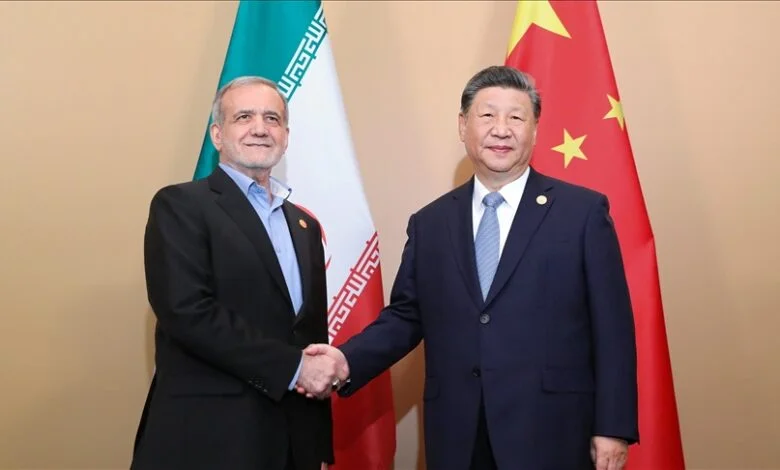

The signing of 20 documents on cooperation between the two countries in various fields, including international trade, information technology, intellectual property protection, media, agriculture, tourism, health care, sports and culture in February 2023 by the late Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, was the culmination of these relations, reflecting a clear desire to diversify cooperation beyond the traditional sphere.

The "Comprehensive Strategic Cooperation Agreement" signed in March 2021 is one of the most important turning points in this relationship, which stipulated a 25-year time frame for strategic cooperation, under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative, and included joint projects in the fields of energy, infrastructure, ports, transportation, the financial sector, and telecommunications, in exchange for a long-term Iranian commitment to provide oil supplies to China at preferential prices, as well as a long-term Iranian commitment to provide oil supplies to China at preferential prices. Public estimates of potential Chinese investments in Iran have reached $400 billion.

These agreements come at a time when China seeks to secure new and stable energy corridors and strengthen its presence in West Asia in the face of the US cordon stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the Middle East. As for Iran, it sees Beijing as a partner capable of breaking international isolation and easing the impact of US sanctions that escalated after Washington's withdrawal from the nuclear deal in 2018.

The Chinese role in the UN Security Council has emerged as an important factor of support for Tehran, whether by rejecting Western sanctions projects or defending Iran's right to use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, which has strengthened Iranians' confidence that Beijing views them as a pillar in a multipolar international system, not just as a source of energy.

Despite this rapprochement, however, the Chinese side has remained conservative in dealing with major security crises linked to Iran, preferring diplomatic caution to direct engagement, especially with regard to the Israeli file, the Arabian Gulf, and the Red Sea.

Beijing preferred to stick to a "diplomatic caution" approach and avoid military alignment, which was clearly evident in China's balanced stance on the recent escalation between Tehran and Tel Aviv.

China's position on escalation

With the outbreak of military escalation between Iran and Israel in June 2025, China adopted a traditional diplomatic stance, calling for "restraint" from all parties and emphasizing the need to "resolve differences through dialogue and negotiation," without directly condemning Tel Aviv or holding it responsible.

The first official Chinese comment came from the Foreign Ministry spokesperson, who stressed that "maintaining regional stability is in everyone's interest," in what appeared to be a calculated balance: Beijing does not want to lose Tehran, but it also avoids provoking Israel or engaging in a direct confrontation with Washington in a highly complex region.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi also emphasized that China is in contact with Iran, Israel and relevant parties and looks forward to seeing a "real ceasefire," and that all parties should resume dialogue and return to the path of political settlement of the Iranian nuclear issue.

This balance comes within a Chinese foreign policy based on neutrality and refraining from military alignment, with long-term economic and diplomatic engagement. China sees itself as an international power keen on stability, not a party to long regional conflicts that may drain its interests, and has preferred to distance itself from any sharp alignment, merely reiterating its opposition to the policy of unilateral sanctions and its rejection of the use of force in international relations, without providing actual support to Tehran in the face of military escalation.

In essence, this caution reflects China's priority to protect its interests with all parties, which makes its position on the current crisis a real test of the limits of its alliance with Iran and its ability to reconcile its anti-US hegemony rhetoric with its complex relations with regional and international powers in the Middle East.

Essentials for deepening the relationship

A combination of geopolitical and economic factors is pushing China to consider deepening its relationship with Iran, not only as an energy or trade partner, but as part of the reshaping of international balances in the face of US influence.

Iran is a major player in the energy market. Before the sanctions, it was one of the largest suppliers of oil to China, and despite low official figures, China continues to import Iranian oil in indirect ways.

China is Tehran's lifeline from international sanctions; Beijing buys more than 90% of Iran's oil exports, with China importing 1.3 million barrels of Iranian crude per day in April 2025.

This interdependence is not limited to oil purchases, but extends to China's efforts to reduce its dependence on US-influenced energy suppliers by building an alternative network that includes Iran, Russia, and Venezuela, and is part of its strategy to hedge against any Western strangulation of its economy.

Iran is important for the expansion of BRI projects, as it forms a strategic link, especially through the Chabahar port and the Kashgar-Tehran-Istanbul road. Through infrastructure development, rail and road connectivity, China has sought to make Iran a major logistics platform connecting Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

Beijing has made major investments in this direction, including railroads such as the $1.5 billion Tehran-Mashhad train project, solar power plants, and infrastructure projects that have exceeded $5 billion since 2007, making Iran a geostrategic link that cannot be compromised.

China fears that in the event of the collapse of the Iranian regime and the arrival of a regime allied to the United States, the Western blockade will be strengthened, an opinion supported by Chinese researcher Einar Tangen of the Taihe Institute in Beijing in a statement quoted by TRT Global on June 19, 2025, saying that "the fall of the Iranian regime would constitute the nightmare scenario for Beijing," adding that China has warned that the collapse of the regime could lead to an explosion of the regional crisis, disrupt energy supplies, and threaten its major projects such as "the Belt and Road."

The issue of energy and oil is one of the strategic matters that China seeks to obtain to complete the modernization process, after it became the second largest importer of oil in the world after the United States, and as much as China seeks to secure its interests in energy, it also moves to ensure a stable political environment that allows the promotion of major projects, and this was evident in its role in mediating between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which resulted in an agreement to resume relations in March 2023, after years of estrangement.

This move was driven not only by a desire to play a mediating role, but also by the realization that any escalation in the Gulf would undermine its interests and disrupt its strategic projects.

Strengthening the relationship with Tehran is also part of China's broader policy to counter the American encirclement, especially through alternative alliances, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS.

Iran's presence in these platforms gives China geopolitical support in the face of growing Western alliances, and a fulcrum against Western alliances such as QUAD and I2U2, which includes Israel, India, and the United States.

In addition, China is aware that any security chaos in Iran could spread to its western neighbor, namely Pakistan and Afghanistan, which could threaten the stability of the Belt and Road's energy corridors and infrastructure, especially in sensitive areas such as Balochistan.

Pakistan shares these concerns with China. During his meeting with US President Donald Trump at the White House on June 16, 2025, Pakistan's army chief Asim Munir expressed fears that separatist militants and jihadists on the Pakistan-Iran border could take advantage of any collapse of power in Iran.

These concerns come after a series of large-scale attacks by separatist groups in Pakistan's southwestern Balochistan province in 2024, prompting Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif to warn that these attacks were aimed at undermining the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), one of the most sensitive Belt and Road projects.

All these factors make Iran a partner that cannot be ignored in Chinese calculations, even if this partner has not yet turned into a political or military ally in the explicit sense.

The limits of Chinese support for Tehran

The limits of Chinese involvement in the Iranian-Israeli escalation cannot be understood in isolation from the intertwining of Beijing's economic interests with both Israel and the United States, as China, which categorizes Iran as a strategic partner, considers Tel Aviv to be an important economic and technological partner.

According to Israeli Ministry of Economy data, the volume of trade between China and Israel reached $25.5 billion in 2022, including Israeli exports worth $4.7 billion, including vital sectors such as agricultural technology, cybersecurity, and advanced medical equipment.

In contrast, Chinese companies are investing in strategic infrastructure projects inside Israel, such as operating the Haifa port and expanding the port of Ashdod, as well as companies in the telecommunications and urban transportation sector, despite US pressure on Tel Aviv to curtail technological cooperation with Beijing.

This economic rapprochement forces China not to appear as a direct adversary of Israel or an outright supporter of Iran in any military conflict, even if Beijing opposes Tel Aviv's policies on issues such as the Palestinian issue and the Iranian nuclear file, it practices double diplomacy, political reservations that do not translate into economic estrangement or military alignment.

On the other hand, US markets remain centrally important to China, especially in the technology, finance and trade sectors, and as the trade war between Beijing and Washington escalates, any clear siding with Tehran could cost China dearly, such as economic sanctions, technology restrictions, or even losing the support of global partners in the Global South who do not want to be lumped into closed camps.

Therefore, China's stated support for Iran is limited to non-hard power tools, embodied in trade, limited investment, political support in international forums such as the United Nations and the Security Council, coordination through frameworks such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS, and sometimes defending it against unilateral sanctions or Western criticism without moving to a security or defense partnership.

Despite the apparent strategic rapprochement with Iran, China is keen to keep its relationship with Tehran within the ceiling of a "flexible strategic partnership", without security alliances and clear military commitments, but rather coordination based on economic interests and regional stability.

Between U.S. pressure and the web of overlapping relations with Israel, Beijing continues to play the role of a "balanced power" that maintains channels of communication with all parties, betting more on stability than alignment, without reducing itself to any specific regional axis.

China and Russia's approach to the escalation

Both China and Russia took similar positions in officially rejecting the Israeli attack on Iran, but they differed in degree, style and diplomatic repercussions, as the Chinese position was more balanced and cautious, as the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson called on all parties to exercise restraint and favor diplomatic solutions, without naming Israel or openly supporting Iran and resolving the crisis diplomatically.

China, along with Russia and Pakistan, supported a Security Council resolution calling for a ceasefire without holding Israel responsible.

Compared to China's position on the Russian-Ukrainian war, Beijing has taken a much clearer stance, refraining from calling the invasion an "invasion," directly criticizing NATO, accusing it of being responsible for the escalation, providing diplomatic cover for Moscow in the Security Council, rejecting Western sanctions on Russia, and putting forward a "12-point peace plan" in February 2023.

As for Israel's attack on Iran, as we have shown, it used general and more cautious phrases such as calls for "restraint" and "de-escalation" without naming Israel, and issued no policy initiative, nor any direct condemnation.

In contrast, Russia took a tougher stance and solidarity with Tehran, and strongly condemned the Israeli and American attacks on Iranian sites, stressing the need to respect Iran's sovereignty and its continued cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency, while Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov announced the continuation of support for Iran's peaceful nuclear program.

In an interview with Russia 1, Lavrov stressed that Israel's actions cannot be justified by the right of self-defense, saying: "If every country is allowed to interpret the right of self-defense according to its whims, we are not talking about a world order, but about total chaos," Lavrov said in a direct criticism of Israel's justification of the attacks based on Article 51 of the UN Charter.

Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova called for "understanding what Iran really wants, without external projections," stressing that developing a peaceful nuclear program under the supervision of international institutions is a "legitimate sovereign right."

While China seeks to maintain a delicate balance between its relationship with Iran and its economic interests with Israel and the West, Russia has taken a more clear and solidarity-oriented political stance, without turning into an explicit security alliance and without direct military support.

The comparison shows that China has been more politically engaged in supporting Russia, because it is a strategic partner in confronting the West, while Iran, while an important economic partner, sees no interest in risking a clear alignment with it, especially in a conflict that threatens to ignite the region and put it in direct confrontation with Israel and the United States.

The Future of the Iran-China Relationship

The military escalation between Tehran and Tel Aviv, and the participation of the United States in direct support for Israel, which went as far as participating in the bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities, has put Beijing in front of a delicate equation, the title of which is maintaining its complex interests with all parties, without sacrificing its strategic relationship with Iran, which is a major gateway to its influence in West Asia and a bridgehead in the project to reshape the multipolar international system.

If U.S. and Israeli pressure on Iran continues, Beijing may be inclined to strengthen its support for Tehran in a more engaged manner, but without open escalation. This support consists of expanding infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative, linking them to trans-Asian economic corridors, using the Chinese yuan in oil settlements, reducing Iran's dependence on the dollar and promoting limited dollarization for China, and expanding Iran's membership in Asian blocs.

This scenario establishes Iran as a key partner in the Belt and Road and strengthens China's presence in a region that is witnessing the gradual decline of U.S. influence.

However, Beijing is likely to maintain a flexible partnership model based on expanding economic interests and mutual support in international forums, without moving to an explicit political or military alliance, which guarantees China a diplomatic margin of maneuver with the West and avoids attrition in complex security files that do not serve its trade and development priorities or its major goals.

On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that Beijing will move towards a deliberate move if US pressure escalates or its interests are directly targeted, especially if shipping lines are disrupted or its companies are subjected to cyber attacks in the Gulf or Arabian Sea. At that time, Beijing may find itself forced to freeze or delay some aspects of cooperation with Tehran, especially in sensitive sectors such as communications and energy, if it turns out that the cost of taking sides outweighs its benefits.

In sum, all the moves and developments indicate that the Iranian-Chinese relationship is entering a new phase, in light of the changing global balance of power and the increasing polarization of the new Cold War. While Beijing recognizes the importance of Iran as a strategic partner, at the same time it is keen not to sacrifice its interests in an international system that it has not yet left, but is still trying to reshape from within.